Why Drummers Count And How Counting Can Help You

We’ve all heard that iconic cry of “1, 2, 3, 4!” coming from the drummer before a song starts. This may have left you wondering: does the drummer always count? How do they do it? Why do they do it? Perhaps you’d like to know how you can incorporate counting into your own playing. Well, you’ve come to the right place. Here’s what I’ve learnt about counting rhythm in the 10+ years I’ve been playing, studying, and teaching drums.

Not all drummers count while playing. Counting is a useful tool to set the tempo for a song, understand complex rhythms & time signatures, or to keep your playing in check. Counting is also extremely important as a communication tool between band members.

In this article, we’ll cover:

- Who counts music and why.

- When you should count.

- How to count.

- How to count different subdivisions.

- How to count odd time signatures.

- Tips and tricks to help you count music

Table of Contents

First of all - do all drummers count?

Many drummers use counting in some capacity. Even if just to cue the music in, a verbal reference to the tempo is useful. It’s more common for drummers to count as they often lead the band into songs. However, even those who do count music don’t do it all the time.

For most, counting is a way to set the tempo for your band or learn a complicated rhythm. Constantly verbally or internally counting while you play can be a detriment. It requires additional mental energy that takes away from your own playing and listening skills. That said, this can be a positive challenge for your coordination.

While many people do count, there are more than a handful who don’t. A significant number of drummers use feel alone to play, learning pieces by listening. There’s nothing wrong with this! If it works for you and you’re achieving everything you want in music, go for it. However, I have had many students that didn’t want to count. The moment I convinced them to simply have a go, they saw the benefits.

Why do drummers count?

Counting is useful to musicians for a variety of reasons.

One of these reasons is to count how many bars have passed whilst playing. A bar is essentially a container for a small chunk of music – using them greatly helps to structure and understand songs. For example there might be eight bars the drummer has to play the same drum beat before playing a fill, counting will make sure the drummer doesn’t miss this change.

Another reason – counting within bars – works the same, but on a smaller scale. There might be a complex rhythm in a bar that starts at a very specific time. Counting can help you get that perfect every time.

For some highly technical types of music counting is a must, for example songs with multiple meter changes, odd times, stops and starts and so on. Without counting this type of music the drummer could easily get lost, as well as the other musicians.

Another instance you may find drummers counting is when they are playing a new song they are not familiar with. For example when a drummer is learning a new song or when they are filling in for another drummer with a band temporarily and are not super familiar with the songs yet.

Why learning to count music is super useful!

There are a lot of reasons to start counting music. The first and arguably most important, is communication.

Most Western music is in 4/4 (read as “four”). This means there are 4 beats or pulses in every bar. To communicate this musicians can count each of these notes (also known as “quarter notes”) as “1 2 3 4“.

To break it down even further, for example to count eight notes in each bar musicians will often say “1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and” with the “and” representing a beat between each quarter note. This language is not universal but a massive proportion of counting musicians use it.

Here’s an example of where this is useful:

You’re in a rehearsal. It’s sounding good, but the guitarist’s out of sync on some coordinated stabs.

Communicating exactly where they should be playing those hits without counting is tedious. This usually involves an agonizing session of trial and error until they get it down by ear. Instead, you could simply say “the hits are on 1, 2 and, then on 4”. Done. You’re all on the same page within seconds. Gain an understanding of counting, and problems like this will never stand in your way again.

Secondly, those who can’t count are standing on very weak rhythmic foundations.

If you have no understanding of rhythm, do you really understand how your part functions within the music? Most people who can’t count are relying on musical cues from others or themselves. So when somebody messes up on stage, they’re up the creek without a paddle. Suddenly the thing they were anchoring their playing around is gone, and things can rapidly fall to bits.

If you understand where your parts sit in the song, you don’t have this problem. You can keep chugging along, playing things exactly where they were meant to be played, and wait for others to get back on board.

Finally, counting will speed up your learning to no end.

Simply listening and repeating until you think you have the part right is a slow way to learn. With counting, you can lay out exactly where each note sits in the rhythm. You can then practice it note by note as slowly as you would like.

Practicing this way is incredibly effective, and is absolutely the fastest way to learn something new.

Getting it correct – slowly – from the start gives you the coordination and ‘muscle memory’ needed to play it quickly. This is especially true when it comes to complex rhythms and unusual time signatures. Playing 13/8 through feel alone is not easy!

How to count drum beats and notation

To begin using this incredible tool in your own playing, it’s important you understand the fundamentals. The basic language of counting in the context of a standard 4/4 bar is as follows.

| Quarter notes | “1, 2, 3, 4” |

| Eighth notes | “1 + 2 + 3 + 4 +” (“+” spoken as “and”) |

| Eighth note triplets | “1-trip-let 2-trip-let 3-trip-let 4-trip-let” |

| Sixteenth notes | “1e+a 2e+a 3e+a 4e+a” (“e” pronounced like for “ear” and “a” as “uh“) |

Try playing two bars of each note type (or “subdivision”) to a metronome whilst counting to begin internalizing these.

Once you’ve got the hang of counting whilst playing, start mixing up the order. You could try going backwards from sixteenth notes, randomly up and down the table, and even start changing beat by beat. The main goal is to associate the note values you’re playing with the sounds coming out of your mouth.

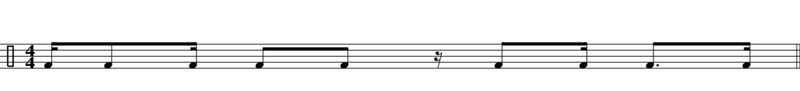

Once you’ve played with this idea for a while, it’s time to start applying it to learning. Below is a rhythm for you to try out.

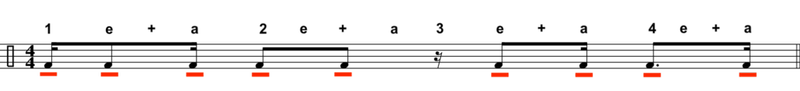

This may look quite complex, especially if you don’t read music! However, trust me when I say it’s easy with counting and some slow, deliberate practice. Below is the exact same rhythm with the phonetic counting laid out above it. Count the whole thing out loud slowly, playing only the highlighted syllables.

Much easier, right? This is why counting is so useful for learning. Next, you can try counting only the notes you play. At faster tempos, counting a full bar of sixteenths will quickly take your breath away!

Next, try counting over any beats or fills you’re already comfortable with. Start with something very simple, like the basic Rock beat. Follow that up with any simple fill you enjoy playing. Soon enough it’ll feel natural and you’ll be glad you did it.

How to count different time signatures

So, that’s counting in 4/4. What happens when we hit a different signature, like 6/8? The pulse is made up of eighth notes here; what on earth do we count? Surely not “1 + 2 + 3 +”?

Most people count the pulse in eighth note time signatures (6/8, 7/8, etc.) with numbers alone. For example, 6/8 would be “1 2 3 4 5 6”. If you are playing any sixteenth notes, you would count them “1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 +”.

There is a reason we wouldn’t count 6/8 in the same manner as 4/4 (i.e. “1 + 2 + 3 +”). If we were to count the bar this way, it would change the feel to that of 3/4. This means that there would be an implied emphasis on the quarter notes (“1, 2, 3”). In 6/8 the notes are seen as being more evenly stressed. Confused yet? I know I was!

It’s easy to see why this topic can get a bit mind-bending at times. At the end of the day, counting and time signatures are subjective. The only reason they are there is to put names to beats. As we’ve found out, this can be tremendously helpful with a whole host of things. Just remember: there is technically no right or wrong. Any time signature can be counted in any way if it makes sense to you. Any “correct” way of counting is just what makes the most sense to most people.

Does it make sense to count 4/4 in groups of 17? Of course not! Could you do it? Sure! It’s all about what helps you play better, communicate more efficiently, and learn faster. The established counting language is simply the consensus on this.

Tips and tricks to help you count

Now that we have the basics down, I want to share a few nuggets of wisdom that have helped me over the years.

1. A cheat’s way to count odd time

Odd time signatures, especially when played at faster tempos, can be tough. They feel unnatural at first and require a lot of mental effort to master. Here’s a little trick that helped me with this.

Let’s say we’re in 7/8. The usual way to count this would be “1 2 3 4 5 6 7”. Instead, you can try counting “1 2 3 4” with the last beat cut short by an eighth note. This requires fewer syllables and thus less concentration. In turn, you’ll (hopefully) be able to feel the time more naturally and learn faster.

An alternative counting hack is to split the bar up into smaller groups. For example, you could count 7/8 as “1 2 1 2 1 2 3”. This is useful for understanding the feel of unusual beats. As you can imagine it is less helpful for counting bars, or musical phrases longer than one bar.

2. Counting bars with beats

This is a method for counting bars whilst keeping track of the beats simultaneously. It’s a simple concept that can be quite a tongue twister! While you count the beats, increment the first beat of every consecutive bar by 1. For example: “1, 2, 3, 4, 2, 2, 3, 4, 3, 2, 3, 4” etc.

This method makes it easy to note down the length of sections. It also gives you awareness of where things are happening within the bar. Maybe the section doesn’t change on the “1” of the first bar, it changes on the “4” of the previous one. This way, you’ll know.

3. Shorten everything to one syllable

Counting quickly up to 6 is a cakewalk. However, as soon as you hit the sevens, elevens, thirteens, etc. it becomes quite taxing! This is because these are all two-syllable words. To make this easier, you can shorten them to their first syllable only. For example, seven becomes “sev”. Doing this is quite difficult initially but you’ll get it with some practice.

4. Say it before you try to play it

This is less of a tip on how to count, and more another way it can help you. My first teacher always used to say “if you can say it, you can play it”. This has rung true throughout my entire drumming career. Being able to count something out loud before you try to play it, helps a lot. We’re used to speaking with rhythm as we do it all the time. This could be why it’s helpful to internalize a rhythm through speech first. Once you have it, playing it with your hands or feet is far easier.

Conclusion

Counting might seem complicated at first but when broken down it can be quite simple to learn.

I highly recommend you practice counting while playing as once you’ve mastered this it will become a great tool you can use to both learn quicker and to communicate with other musicians more effectively.

Who we are

AboutDrumming.com is run by a group of drum teachers, drumming professionals and hobbyists. We love all things drums, and when not drumming we spend our time adding more awesome content to this website!

Free tools

You may also like

Affiliate Disclosure: When relevant AboutDrumming.com uses affiliate links (at no additional cost to you). As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.